Every gardening article talks about how growing your own food provides you with great-tasting produce while also saving you money. And while there’s no doubt that homegrown tomatoes taste better than shop-bought ones, one question still stands: does growing your own vegetables actually save money? Or is it just some bogus narrative to help gardeners cope with the sunk-cost fallacy at the end of the growing season?

The only way to find out was to put theory into practice. So in 2024, I set out to make a little experiment. And after a whole year of filling spreadsheets and doing the maths, this is what I found out:

I was able to save almost £810 by growing my own food, mainly on produce like tomatoes, berries, and herbs. In comparison, I only spent about £390 on fruit and veg. I grew over 140 kilos of food, including crops you wouldn’t usually find in a supermarket. And thanks to careful planning and succession planting, I was able to harvest something from my garden every week of the year, regardless of the season.

So let’s take a closer look at how growing my own fruit and vegetables worked out for me, and whether it’s worth giving it a go yourself.

The Setup

The study took place on my allotment plot in Kent. I took on a plot in March 2023, then spent most of the year tidying up and setting up, and trying to figure out what works and what doesn’t. And by the time 2024 came around, I was ready to start tracking my savings.

The powerhouse of my plot is a 70 square meter section divided into 16 two square meter beds. Now, you don’t have to use raised beds (they cost a lot to set up, and they always require a lot more compost than you think). Personally, I use them because they make it easier to keep organized, they allow me to build protective structures, and I simply like the way they look.

70 sqm may not sound like much, but this small space (which frankly is roughly the size of an average urban garden) allowed me to grow more than 40 different crops.

What Are the Best Crops to Grow To Save Money?

Always grow the food you want to eat. For example, Tuscan kale is stupidly expensive, considering how easy it is to grow and that you can get repeat harvests from one plant. But if you or your family don’t eat it, then what’s the point in growing it?

But let’s let the numbers do the talking. Based on my 2024 figures, these were my top 10 money-saving crops:

| Crop & cultivar name | Weight (kg) / year | Savings (£) / year |

| Tomatoes (n/a) | 19.98 | 172.00 |

| Fruit (strawberries, blackberries) | 6.64 | 88.30 |

| Leeks (Porbella) | 8.02 | 75.71 |

| Cucumbers (Marketmore 76) | 6.66 | 69.89 |

| Herbs | n/a | 35.89 |

| Courgette (Primula) | 11.36 | 34.62 |

| Kale (Cavolo Nero) | 6.07 | 32.75 |

| Beetroot (Boltardy, Burpees Golden) | 6.21 | 32.25 |

| Purple sprouting broccoli (Claret) | 3.13 | 29.6 |

| Parsnip (Countess) | 19.85 | 23.5 |

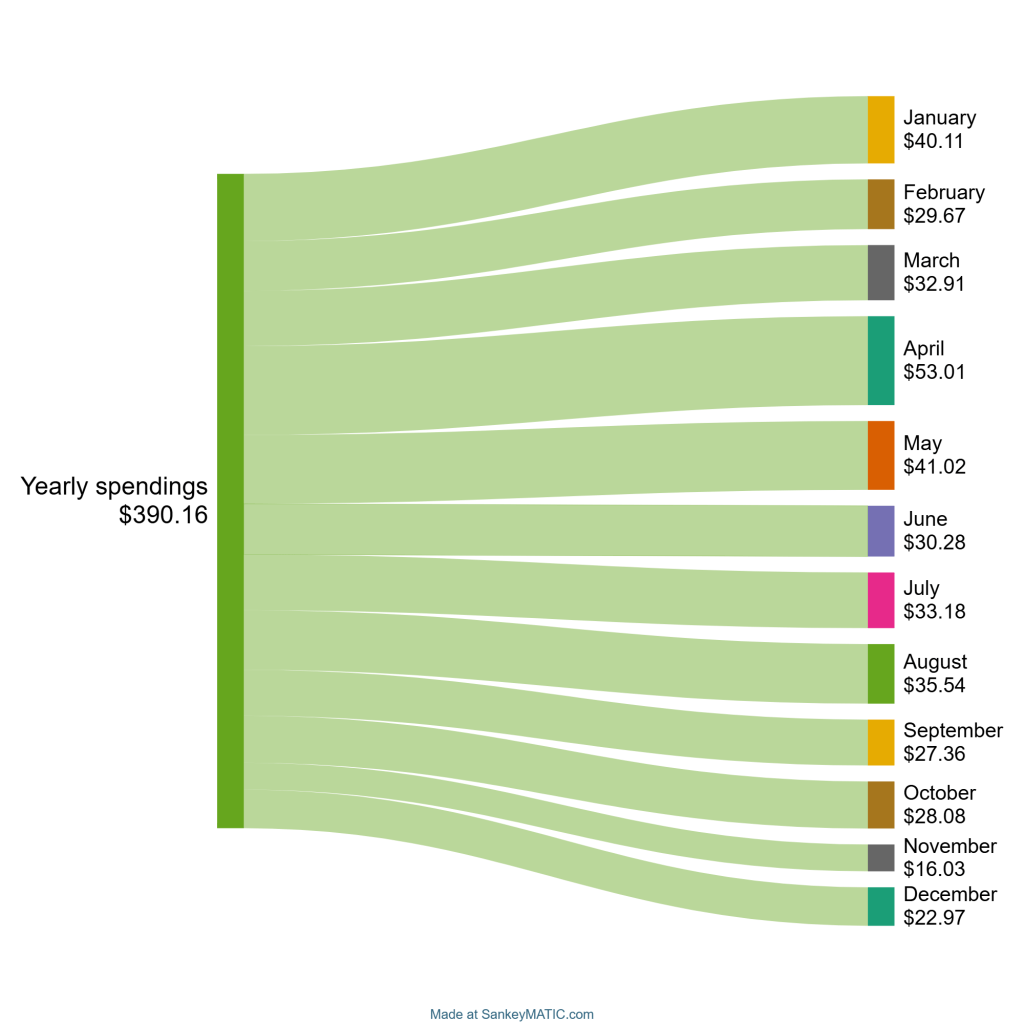

In comparison, this is what my veg spending looked like in 2024:

Now, the reason this worked out so well for me is because a lot of thought went into the types of crops I planted, as well as the specific cultivars. So I want to take a moment to talk about the top 5 best-performing crops — starting with the obvious:

1. Tomatoes

Everyone should try to grow their own tomatoes. Shop-bought ones are not only crazy expensive but also bland. I think a lot of people overcomplicate growing them and, to be fair, most growing guides tend to make matters worse by claiming they’re easy to grow, then overwhelming the reader with info (most of which is only there for SEO purposes — ask me how I know).

So I’ll make it simple. Grow cherry tomatoes. Yes, I know, beefsteaks are great on a sandwich and plum tomatoes are great for sauces. But if this is your first foray into tomato growing, just go for the cherry ones. They have high yields, suffer fewer issues with splitting and blossom end rot, and because they ripen faster, you’re more likely to get a nice harvest before either the cold weather or late blight kills them off. My favorite is Sungold (they perform very well outdoors), but last year I also enjoyed Tigerela and Chocolate Cherry.

2. Fruit

Specifically, strawberries and blackberries. Supermarket berries make for such a sad eating experience they should be illegal. They’re usually underripe when picked, which means they’re bland and watery. Not only are they expensive, but they also tend to go soft and moldy in a matter of days just sitting in the fridge. At this point, growing your own is simply a no-brainer.

In my case, I only grew 4 strawberry plants ( an ever-bearing cultivar called Elan) and two alpine strawberry plants. My plot is surrounded by blackberry hedges which are, frankly, annoying the life out of me (they’re incredibly invasive), except for a month or so in summer when their fruit is at its peak.

While you’re at it, I also recommend growing rhubarb. It’s a very hardy perennial, and one of those things that costs way too much money in the shops.

3. Leeks

I feel that leeks don’t get enough love. I’ve praised their neverending virtues in the past, and I’ll happily do it again. They are a fantastic substitute for onion, they’re easier to grow, and are always unreasonably expensive. You can start harvesting them as soon as they’re the width of a pencil, and because they’re frost-hardy, you can enjoy them for months on end. In 2024, I picked them from January until mid-February, had a gap during spring (when I ran out and had to wait for the new plants to grow), then started picking them again in June. And at the time of writing this, I still have 1/4 of a bed of leeks ready to be harvested.

4. Cucumbers

This was my first time growing cucumbers, and it was a tremendous success. The main reasons I decided to grow them were the fact that I can’t abide the condom-wrapped stuff you get in shops, and because I wanted to make pickles. Now, most supermarkets don’t stock gherkins, so you have to look for them in specialty produce shops. And much to my dismay, they always cost more than I’m willing to spend.

The variety I grew is Marketmore 76. I picked it because you can grow it outdoors (where it performed beautifully even during the abysmal summer of 2024), it’s a heavy cropper, and it’s versatile (you can use it as either a slicing cucumber in salads, or turn it into pickles). I grew just two plants, and although they only cropped from mid-August until the end of September, they were so prolific we’re still enjoying them as pickles.

5. Herbs

Herbs are the easiest crop to become self-sufficient in and save money. You have so many options: you can grow them in pots on a windowsill or straight in the garden, you can go for annuals (cilantro, basil, oregano, etc.) or perennials (rosemary, sage, chives, mint, etc.). Plus, you can either use them fresh, or preserve them through drying, freezing, and mixing with butter or oil.

My advice is to try and buy small, potted plants rather than growing from seed. It’s faster and more likely to succeed. Also, I recommend buying potted herbs from the supermarket rather than a garden center. They’re usually bigger, and also cheaper.

There’s one thing I didn’t grow but deserves a mention: lettuce. I’m not a fan of it, but if it’s something you regularly enjoy, then do give it a go. It’s easy to start from seed, and even though it tends to bolt in the heat, you can plant it again in late summer and, with a bit of frost protection, enjoy it throughout winter. Also, it costs a fortune pretty much everywhere so yeah, definitely grow your own.

The Importance of Intercropping and Succession Planting

One of the things that helped me maximize my space and ensure repeat harvests was planting different crops in the same bed, and making succession plantings.

For example, I planted several first-early potato beds at the beginning of March, then harvested the new potatoes by the end of June. The same beds were then used to grow tomatoes, with sweet potatoes as a cover crop/living mulch.

I also like to grow radishes in between other plants. They’re a fantastic spring and fall crop, they don’t take up much space, and can take just one month from seed to harvest. You can also use this method for crops like spinach, spring onions, carrots, or bok choy, all of which can be planted both in the spring and in late summer.

Crops That Are Not Worth Growing To Cut Down Costs

A few examples come to mind, but I’ll only pick two: onions and potatoes. These crops are always cheap and easy to find in supermarkets, so growing your own to save money is absolutely not worth it. I harvested 12.5 kilos of potatoes in 2024, which saved me a whooping £16.25. Also, the taste difference between shop-bought and homegrown is not enough to justify going the extra mile.

Onions in particular are surprisingly difficult to grow at the best of times, but particularly nowadays thanks to the erratic weather patterns caused by climate change. A lot of people on my allotment grow onions. They plant them in the spring, then come June we either get a sudden cold snap, or people forget to water them, and by late summer the onions are all small and bolting. Hardly worth the time and effort — just grow leeks instead.

I will admit that I do grow spring onions, because they’re easier to look after and they cost a pretty penny. I also grow potatoes because I like red-skinned new potatoes (particularly Red Duke of York), which you rarely get in the shops. Bonus pro tip: if you have an allotment, potatoes are a great way to make your plot look like you’re growing stuff, especially if it’s your first year as a tenant and the annual inspections are coming up.

I should mention that out of the £390 I spent on veg in 2024, most of it went on bell peppers. I eat a lot of the stuff. Realistically, if I cut them out of my diet I could reduce my spending by half, but alas, I like them too damn much. Would I be better off growing my own? Absolutely not. I don’t have the space, the climate, or indeed the inclination to waste my time and resources on a crop that I could just buy year-round in the shops. Sometimes you just have to figure out where your priorities lie.

How Much Does It Cost to Grow Your Own Food?

Allow me to be frank: most discussions concerning the cost of growing your own food are not helpful. There are just too many variables: where do you live, do you have a garden or are you growing stuff in a flat, are you growing straight in the ground or in pots / raised beds, are you starting from scratch or do you already have a gardening setup? Trying to give an exact figure is simply too case-specific.

Also, I can’t help but notice that there’s a bit of a defeatist attitude about this question. I feel that a lot of people are wary of growing their own veg because it seems like such a daunting, expensive, time-consuming task, and there’s no real point in even attempting it if you’re not going to at least break even by the end of the growing season. Everyone knows the memes about spending $100 to grow $2.50 worth of tomatoes. And yet everyone is keen to discard the things you can’t put a price tag on, such as the joy of engaging with nature and the growing process, the unparalleled taste of freshly picked homegrown produce, or simply learning a valuable skill.

And for some reason that I simply cannot fathom, people always get bogged down talking about the cost of seed. Yes, some seeds are expensive (especially if you want to grow fancy tomatoes). And with some crops (such as carrots and parsnip) it’s better to buy fresh seed every year. But unless you want to grow 400 kale plants, 75 beans, 20 courgettes, 1,200 lettuces, and 1,700 turnips (which is the average number of seeds you get per pack), you’ll have more than enough seeds to use in the following years.

But what really irks me about this argument is that it seems to only exist for the sake of arguing. For instance, everyone agrees that cooking at home is a great way to save money. Yet how often do you hear people ask: “What about the cost of cooking your own food? I don’t have any pots and pans or cooking utensils, I’d have to spend money on that. And what about gas and electricity, or the time it takes to cook everything and do the washing up? Nah I’m better off ordering takeaway.” That’s a daft way of looking at it.

It’s the same with growing your own food. Yes, there will inevitably be initial costs. But unless you plan to pack up shop at the end of the season and never grow a slip of carrot ever again, you will reuse the equipment you invested money in. You may not break even in the same year, but you will see a drop in your overall expenses in the years to come.

Now, my rant is probably just as frustrating as the question I’m trying to avoid, so for the sake of the argument, I will try and humor you.

I spent at least £1,000 on my gardening setup when I started in 2023. My allotment was a (weed-infested) blank canvas, so I had to spend money if I was to grow anything. I think I spent £200 on building raised beds alone, and another £150 on two tons of compost. There were also a lot of unexpected expenses, and I think I spent at least £150 on chicken wire to protect my crops from badgers. Plus the cost of tools, seeds, bamboo canes, fleece, netting, PVC pipes, metal brackets, fertilizers, nematodes, etc etc.

However, 2024 was drastically different. I asked my friends and family for garden center coupons for my birthday and Christmas, so that covered much of my costs. I used lots of straw, wood chips, leaves, and grass clippings to mulch my beds, which increased the organic matter available in the beds while also reducing my spending on compost and fertilizers. I had lots of seeds left over from my previous growing season. And even though I still bought liquid seaweed, I made most of my plant feed from the nettles, comfrey, and borage growing around my plot.

The point I’m getting at is that if the main reason you want to grow your own food is to get an instant return on your investment, then don’t bother. You can’t compete with economy of scale. Every December, my local supermarket has an offer where you can get the Christmas roast veg (stuff like carrots, parsnips, potatoes, and Brussels sprouts) for just 15 pence. If my gardening endeavors were cost-driven, I would find this terribly disheartening. Alas, I genuinely enjoy gardening and being able to pick fresh produce throughout the year, so I don’t dwell on these details.

Also, be honest with yourself. If you read this far into the article, I’m willing to bet that you’re seriously considering growing your own food. So why not just do it? Even if all you do is grow a few windowsill herbs or a tomato plant. Worst case scenario, it could be a monumental failure. But then again, it might not. Only one way to find out.

Methodology

The study took place between January 1st and December 31st 2024 in Kent, United Kingdom (roughly the equivalent of USDA zone 8). The participants were two adults. While not subscribing to any particular diet, most of the meals we consumed were vegetarian.

The prices of the fruit and vegetables were compared to those of the supermarket chain Sainsbury’s, which is where we usually do our shopping (with a few exceptions such as fresh gherkins, golden beets, or lovage). The prices do not take any offers, promotions, or loyalty discounts into account.

The fruit and vegetables were weighed and added to a spreadsheet at the time of harvesting, not the time they were consumed. The spreadsheet does not take into account any produce we picked and processed the previous year (such as pickles, pesto, and herb butter), or crops for which we couldn’t find any suitable pricing alternative (such as chive flowers, nasturtium seed pods, and herbs like bronze fennel and santolina).

I want to point out that 2024 was a terrible year for gardening in the UK. We had a mild and wet winter, which did help us get more produce in winter and early spring. However, it also meant we had bigger struggles with pests, especially slugs. We saw an increase in pests such as flea beetles and woodlice (which affected our carrots and Brassicas), and were faced with allium leaf miners (a new pest on our allotment). It was unusually cold and we had light frosts as late as June, which meant that we transplanted some of the heat-loving plants (like pumpkins and courgette) almost a month later than we did in 2023. Lastly, summer was very dark and wet, which meant that a lot of crops that were very successful in 2023 (mainly runner beans, pumpkins, courgettes, and sweet potatoes) struggled. Under different circumstances, our yields would have been much higher, and we would have realistically saved at least £1,000 and spent significantly less on fruit and veg.

It’s also worth mentioning that a lot of our diet was supplemented by foraging for things such as wild garlic and, most importantly, mushrooms. So if you want to learn more about saving money on food, do check out my beginner-friendly guide to mushroom foraging.